Enhancing Sustainability in ODA Capacity-Building: Designing Learning and Change Beyond Training

This article draws on extensive practical experience designing field change in corporate training, as well as accumulated observations from directly planning and implementing capacity-building programs in international development contexts. Although these two areas differ in context, they show remarkably similar limitations when confronted with the question: why does learning fail to lead to real change?

Introduction: Perspectives and Analytical Framework on ODA Capacity-Building

Why revisit capacity-building in ODA now?

This article revisits capacity-building—a long-standing core instrument in ODA—beyond the conventional focus on individual competency. It considers capacity not only at the personal level but also at organizational and institutional levels, from a sustainability perspective. The aim is to systematically present ways to design programs that leave tangible change in the field, moving beyond training-focused approaches.

Rather than offering a simple summary or declarative critique, this article examines why existing practices were established and where they reached their limits. Using insights from performance technology, field-centered instructional design, learner experience design (LXD), and design for field application and transfer, it explores how capacity-building can be reconfigured through concrete decision units and structural design. Importantly, this discussion assumes that such efforts must integrate closely with performance management across the ODA project cycle, not just with training itself.

In the private corporate training sector, approaches combining performance-based design, field application-centered instructional design, and LXD—through action learning and project-based learning—have been widely applied. These approaches prevent learning from remaining a simple knowledge transfer, connecting it instead to behavioral change and performance outcomes in real work contexts. While widely applied in corporate and educational contexts, these principles are also applicable, in principle, to ODA projects.

The Expanded Concept of Capacity-Building in International Development

In international development, “capacity building” or “institutional strengthening” has long been a central discussion topic. Organizations such as UNDP and OECD DAC define capacity building not only as education and training but as strategic interventions encompassing organizational structures, decision-making systems, institutionalization, and sustainability. Nonetheless, in literature and project practice, individual learning-centered, one-off training approaches often remain dominant. While discourse emphasizing sustainability and on-the-ground change has expanded, the design language and operational structures necessary to implement these principles are not yet fully established.

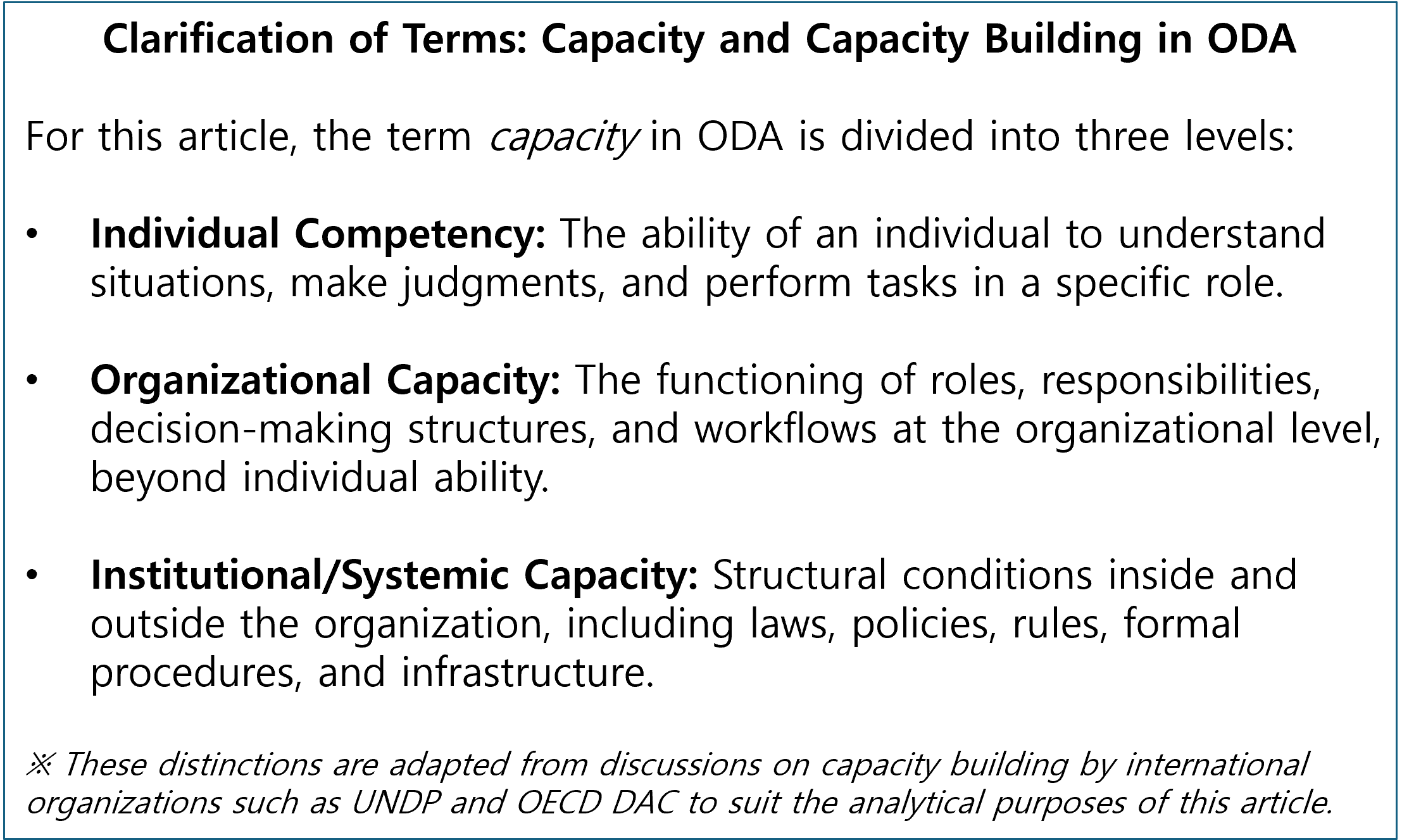

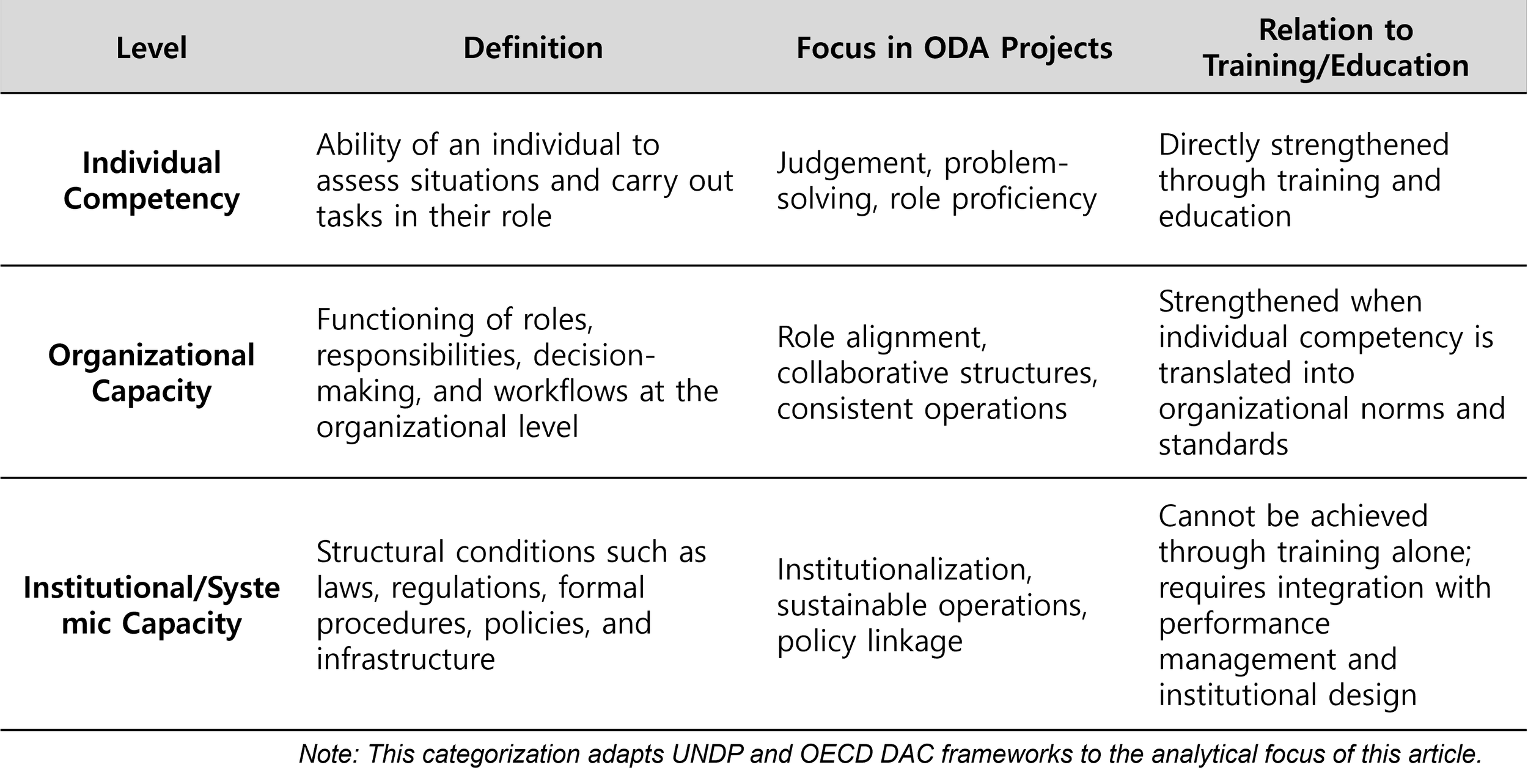

Capacity building in international development is understood as the simultaneous enhancement of individual competency, organizational capacity, and institutional/systemic capacity. Individual competency refers to a person’s ability to perform their role and make decisions. Organizational capacity encompasses how roles, responsibilities, decision-making, and work processes function at the organizational level. Institutional/systemic capacity includes laws, regulations, formal procedures, infrastructure, and environmental conditions. ODA projects inherently aim to strengthen all three levels of capacity simultaneously, making it difficult for the outcome of any single activity to represent the project’s overall achievement.

Capacity-Building in the Korean ODA Context

In practice, Korean ODA often translates “capacity building” as 역량강화, which, despite encompassing organizational and systemic capacities, is frequently used interchangeably with education and training aimed at enhancing individual competency. This practical choice is influenced by the relative ease of designing and implementing education, and the ability to demonstrate visible outputs within a short timeframe. Conversely, organizational or systemic changes are often limited to design or material setup, without implementation or institutionalization during the project period. Consequently, under the label of capacity building, activities focused on individual training are repeated, creating a structure where education dominates.

Problem Awareness and Analytical Perspective

This article does not evaluate ODA capacity building merely on the completeness of training programs. Instead, it reviews how individual competency development through education can connect to organizational and institutional/systemic capacities, ultimately contributing to project outcomes and sustainability. Thus, in the following discussion, education and learning are treated not as independent interventions but as components situated within the broader performance structure of an ODA project.

Based on this framework, the next section examines the historical and structural experiences shaping Korean ODA’s approach to capacity-building, clarifying the context in which current practices emerged and where their limitations lie.

I. Korean ODA, Sustainability, and the Re-examination of Capacity-Building

This section examines why capacity building has long remained a core mechanism in Korean ODA, based on the country’s unique historical and experiential context. It outlines how Korea’s development experience, transitioning from an aid recipient to a donor, has shaped both the perspectives and assets informing ODA design. It also highlights the emergence of sustainability as a central criterion in ODA. Through this contextual review, it becomes clear that the discussion of capacity building in the subsequent chapters is not merely about individual educational or training interventions, but fundamentally concerns how individual, organizational, and institutional capacities can be connected and accumulated—a question closely tied to the identity of Korean ODA.

From Recipient to Donor: Korea’s Unique Starting Point

Korean ODA carries meaning beyond financial support. Korea transitioned from being an aid recipient to a donor in a relatively short period, accumulating development experience along the way. Industrialization, institution-building, and administrative capacity formation involved not only external resources but also policy advice, technology transfer, and human resource training—creating a complex legacy shaping contemporary Korean ODA.

Thus, Korean ODA has emphasized how development cooperation can be delivered rather than how much is provided. Short-term measurable outcomes are secondary to shared experiences of trial, learning, and decision-making during implementation—an approach emphasizing process and judgment accumulation rather than mere replication of completed models.

The Key Question of Sustainability

Sustainability is not an ancillary concept but a critical measure of ODA success. Post-project, the key question is not what was left behind, but who can make what judgments and take what actions in which contexts. Buildings, equipment, and systems age or become obsolete, but decision-making frameworks and problem-solving practices accumulate within individuals and organizations, influencing future choices.

Therefore, capacity-building is central to sustainability. Korean ODA projects have historically included training and learning components, reflecting the recognition that development was enabled through human and organizational learning. However, such capacity-building historically focused more on delivering training than on designing for observable field change.

Recurring Questions

ODA practitioners often ask:

“After all the training, what remains?”

“Participant satisfaction is high, but why hasn’t field practice changed?”

“How did this training contribute to project objectives?”

These questions do not deny the need for capacity-building but probe how it tangibly contributes to sustainability. Historically, previous approaches were rational given limited information access and high dependence on expert-led training. Today, while individual knowledge and awareness change, organizational decision-making and workflows often remain static. The critical issue is not quantity or expertise in training but how capacity-building is designed and connected to systemic change.

II. Training Was Delivered, But Change Did Not Last: Structural Limits of ODA Capacity-Building

Building on the problem awareness raised in the previous chapter, this section structurally analyzes why capacity-building activities conducted under Korean ODA have repeatedly remained at the level of individual learning. Even though education and training were adequately provided, the knowledge acquired often failed to translate into changes in organizational judgment and work practices. This is not due to participants’ lack of will or ability, but rather to limitations in the design structure itself. By examining these conditions, we can clarify why traditional capacity-building approaches are inherently vulnerable to failing in ensuring sustainability.

Training That Remained at the Individual Learning Level

Until now, much of ODA capacity-building has assessed success based on participant satisfaction, shifts in awareness, and improvements in individual understanding. Such metrics are relatively easy to measure and allow short-term demonstration of results, which makes them appear rational. Project completion reports often present the number of training sessions, participant counts, and satisfaction scores as key indicators of achievement.

However, these metrics merely show that training was delivered; they cannot adequately explain how education altered judgment and behavior on the ground. If field staff continue to execute administrative procedures as before after training, improvements in individual understanding do not translate into organizational change. Unless personal learning is connected to organizational standards and work processes, performance evaluation inevitably remains confined to the education experience.

Learning That Disappears Amid Personnel Turnover

ODA contexts are characterized by frequent personnel rotations, organizational restructuring, and external environmental changes. Staff who acquire new perspectives and problem awareness through training may be transferred to other departments or leave the organization after a certain period. While the learning may remain a satisfying personal experience, it is often not shared or institutionalized at the organizational level. Without consistent decision-making standards maintained within the organization, successors are likely to repeat the same mistakes.

This demonstrates that even if training enhances individual competencies, it often fails to convert into organizational learning at the level of decision-making processes and standards. Learning that is not linked to role definitions, operational manuals, or decision-making criteria does not remain as an organizational asset; instead, it moves with the individual. This structural limitation constrains the effectiveness of capacity-building investments in ODA projects aiming for sustainability.

Lack of Mechanisms for Organizational Accumulation

Many ODA training programs are designed around the concept of “what one needs to know,” structured by experts to deliver specialized content to targeted participants. These programs cover both technical skills—such as the use of equipment or laboratory methods—and universal topics like leadership, communication, and project management.

However, such education tends to focus on individual knowledge and skill acquisition. Even when examples connect learning to specific project tasks or organizational operations, these connections rarely translate into standards or structures that can be maintained and accumulated at the organizational level. After training concludes, only materials such as manuals or guides often remain as organizational assets, while the knowledge itself is not systematically embedded in work practices or decision-making structures. In ODA environments, where personnel rotation, organizational changes, and external shifts are frequent, the absence of these links means that learning effects fade at the individual level and fail to strengthen sustainable organizational capacity.

In other words, without a system that allows capacity to be sustainably reinforced, individual competencies strengthened through education remain merely part of the project, rather than contributing to organizational capacity. This creates a structural limitation that prevents securing field-level change and sustainability.

III. Shifting Perspective: Designing Capacity-Building for Field Change

This chapter proposes a shift in perspective to overcome the structural limitations of conventional capacity-building. Capacity-building is redefined not as a collection of training events but as a design challenge aimed at changing the judgments and behaviors repeatedly required in the field. Using performance technology and a role-centered approach, it explains how individual learning can be translated into organizational structures. The focus is no longer on who received training, but on which roles need to make what decisions in which contexts.

Viewing Capacity-Building Beyond Educational Activities

The limitations discussed earlier are not due to insufficient capabilities of implementers but stem from defining capacity-building as a discrete “educational activity.” When training is designed as an isolated event, it is easily detached from the broader logic of change in the project, and its impact often disappears once the program concludes.

Shifting the perspective changes the core questions. Instead of asking, “How many people were trained?”, the focus becomes:

“Which field judgments and behaviors must change through this project?”

“Under what conditions will these changes be sustained?”

From this perspective, capacity-building is redefined as a structural mechanism enabling change, rather than a set of isolated activities.

Performance Technology and Outcome Indicators

Performance technology approaches performance challenges from a systemic perspective. Rather than attributing gaps solely to individual inadequacy and prescribing additional training as the automatic solution, it analyzes whether roles and responsibilities are clearly defined, and whether the information, systems, and environment supporting judgment and performance are in place. This approach helps determine when training is genuinely necessary and when structural changes must precede it.

In ODA contexts, repeating traditional education without simultaneously addressing organizational structures, workflows, and decision-making systems rarely contributes effectively to project goals or sustainability. There are exceptions, such as when the lack of individual competency is indeed the primary issue or when developing key personnel is a deliberate strategic choice. However, in general, achieving stable project results and ensuring sustainable impact requires designing capacity-building alongside systemic change.

A key element in this approach is distinguishing process indicators from outcome indicators. Participation rates or satisfaction scores measure whether training occurred, but they do not capture whether field judgments or workflows have changed. Real impact can only be measured through outcome indicators such as:

How decision-making criteria have shifted,

The consistency of changed workflows,

Improvements in the quality of decisions.

Clear outcome metrics ensure that capacity-building is not merely an activity but a strategically designed and managed core element of the project.

This perspective reframes capacity-building as a mechanism for sustaining change, extending beyond the evaluation of training events. In practice, this requires close collaboration between capacity-building specialists and performance management experts, who often participate separately in ODA projects, to integrate learning with systemic performance improvement.

Translating Individual Learning into Organizational Structures

To achieve sustainability, the focus should shift from individual skills to how those skills function within organizational roles and structures. Capacity should no longer be understood as the sum of individual competencies but as the set of decisions and actions required for a role in specific contexts.

In ODA projects, roles entail distinct responsibilities and decision-making authority, meaning required competencies vary. Most ODA initiatives introduce or transform institutions, procedures, and workflows, rather than merely maintaining existing systems. Early-stage clarification of organizational structures and delineation of roles and responsibilities is essential.

Without this role clarification, training often remains abstract or overly general. Even if content is technical or specialized, its effectiveness is limited if participants do not understand what decisions they are responsible for in the field. Learning stays at the individual level, failing to translate into organizational change.

This is where competency modeling becomes essential. Competency modeling goes beyond listing individual skills—it systematically defines core tasks that must be performed repeatedly for a role, along with the decision-making criteria and behaviors required. In other words, it clarifies what one must be able to do, not just what one knows.

Through competency modeling, individual competencies become measurable and actionable within organizational operations. When role-based competencies are documented and shared across the organization, learning from training is transformed from personal experience into a common language for decision-making. At this stage, organizational capacity-building extends beyond individual learning, integrating into operational structures and practices.

Training Systems Based on Competency Models

Once roles and competencies are defined, training systems can be systematically designed. Training becomes a structured pathway to enhance role performance, including:

Foundational training for new staff,

Advanced learning to deepen expertise,

Field-based exercises to validate competency.

Crucially, training content must directly align with the competency model. Without this alignment, the purpose and outcomes of training are difficult to justify. With competency-based training, performance improvement—not participation—becomes the measure of success.

Standardized competency models and aligned training systems help new staff quickly understand roles and adopt existing decision-making standards, transforming capacity-building from an individual growth experience into an organizational mechanism sustaining operational effectiveness.

Field-Change-Oriented Instructional Design

Defined roles and competency models must function as concrete criteria during instructional design. Field-change-oriented design prioritizes what must change in the field after training over what knowledge should be acquired. Learning objectives are therefore framed in terms of performance change rather than knowledge acquisition.

ODA environments are unpredictable. Instructional design must prepare learners to make decisions under frequently occurring variations, not just follow ideal procedures. Case-based learning, simulations, and field-integrated exercises are essential.

Learning experiences allow participants to recognize their roles and practice decision-making. Content, activities, and evaluation must align with the performance context, enabling training to function as a proxy for real-world practice.

Extending Learner Experience Design in the ODA Context

Learner experience design (LXD) is often misunderstood as a methodology for delivering content more effectively. In the ODA context, learners are practitioners making complex judgments in dynamic environments.

LXD in ODA considers the entire training experience—pre, during, and post—as a single continuum. Pre-training clarifies role expectations and decision responsibilities; during training, participants practice decisions in realistic scenarios; post-training, field application and reflection consolidate learning.

Here, LXD functions not as a micro-level instructional technique but as a high-level principle linking competency models, training systems, and field application. Learning is thus reframed as a continuous process of improving role performance rather than a one-time event.

IV. Sustainable Capacity-Building: Strategies for Design and Implementation

Building on the perspective shift presented earlier, this chapter discusses how sustainable capacity building can be practically applied in the design and implementation of ODA projects. By connecting accumulated discussions from the international community with the experience of Korean ODA, it outlines design strategies for ensuring that education- and training-based enhancement of individual competencies translates into organizational and institutional/systemic capacity. Special emphasis is placed on integrating performance management, mechanisms to sustain field-level changes, and realistic applicability, aiming to create a structure where change endures even after the project concludes.

Linking International Discourse and Korean ODA Experience

Over the past decades, discussions in international organizations and among donor countries have increasingly emphasized moving beyond an individual competency–centered approach to capacity building, toward encompassing organizational and institutional/systemic capacity. This perspective extends beyond education-centered approaches, highlighting long-term outcomes and sustainability rather than short-term results. Principles such as local ownership through participation and co-design, and system strengthening, have also been emphasized. These international discussions clearly recognize the limitations of education-centered approaches.

However, in practice, projects often fail to translate these principles into concrete designs that link individual, organizational, and institutional capacities on the ground. It is difficult to convey through design language who performs which roles, how organizational decision-making structures evolve, and what decision-making standards are left behind. The role–competency–performance–structure linkage emphasized in this article addresses this critical gap.

Redefining Capacity Understanding and Design Units

In ODA, capacity is often interpreted as an attribute of individuals rather than as a structural capability embedded in organizations or institutions. In this framework, capacity is understood as a pattern of repeated judgments and behaviors, and the design unit is defined by roles and performance contexts. While development agencies emphasize ownership—having local actors take responsibility for operations and decisions—linking who will make which decisions after project completion, what will differ from existing decision-making structures, and the role, information, and authority structures that enable these decisions is rarely incorporated as a design unit.

Limitations of Training-Centered Performance Logic

Even when outcomes are mentioned, evaluation metrics for capacity building frequently remain process-oriented, focusing on education participation. Specialized roles within project teams often lead to metrics tailored to each domain, inadvertently reinforcing education-centered indicators.

To connect process indicators with outcomes, education must be complemented with follow-up activities that ensure transfer into practice. For instance, structured on-the-job learning, field mentoring systems, expert coaching, and periodic short reflection sessions are mechanisms that enable capacity-building activities to result in tangible change. In this context, capacity-building specialists must extend their responsibilities beyond course design and delivery to include field application and ongoing learning.

Structural Approaches to Field Change and Sustainability

By linking Korean ODA experiences with international strategic directions, capacity-building design emerges as a structural approach that simultaneously realizes field-level change and sustainability. Sustainable ODA does not mean simply “training more or harder”; it requires establishing from the outset what changes must remain, designing structures that enable these changes, and ensuring they are maintained after project completion.

This requires the integrated application of performance technology, competency models, field-centered instructional design, learner experience design, and mechanisms that promote practical transfer. Such an approach functions as a core mechanism that goes beyond educational effects, creating structures in which organizations and institutions can continuously learn and make informed decisions.

Context Sensitivity and Practical Constraints

ODA operates under significant constraints of resources, personnel, and time, alongside rich cultural diversity. Applying standardized designs without accounting for local culture, organizational norms, and stakeholder dynamics may result in ineffective implementation. Therefore, those designing capacity-building initiatives must understand local and organizational contexts and adapt the design structure to cultural and institutional differences.

Practical constraints must also be acknowledged. In some projects, fully designing and training every role and competency may not be feasible, and education-centered approaches may remain a practical or unavoidable choice. Diverse stakeholders—including donor and recipient countries and international agencies—further complicate ideal implementation. Thus, capacity-building design should be seen as a process of balancing ideal structures with realistic constraints, seeking and executing the best possible design.

Even though proven methods exist in corporate training, ODA capacity-building approaches have often remained bound to past practices. A reluctance to adopt new approaches simply due to a lack of precedent risks missing sustainable change. Experimentation and applied practice in ODA projects are essential for systematically accumulating experience.

Integration with Performance Management

Tight integration with performance management is also critical. Capacity-building activities must be linked to overall project performance indicators. Education and training should be designed based on outcome indicators directly related to project objectives. Activities before, during, and after training, mechanisms to facilitate transfer to the field, and evaluation systems must all function cohesively within the project performance management framework to ensure sustainable change.

Conclusion

In Korean ODA, capacity building can no longer be assessed solely by the quality of educational activities. Capacity should be understood not as an individual’s possession but as a structure in which roles, decision responsibilities, and repeated practices operate within organizations and institutions. Education is merely one means to enable this structure—it is not an end in itself.

Thus, the core of capacity-building design is not how well education is delivered, but whether the learning acquired by individuals is converted into organizational decision-making standards and operational practices. This is only possible when field-centered instructional design, learner experience design, and performance management systems operate together as a unified performance structure.

Ultimately, in ODA, capacity building is a strategic tool for creating organizational and institutional structures that sustain continuous learning and decision-making, rather than merely accumulating individual experience. By drawing on proven corporate training methods and adapting them to the realistic conditions and cultural contexts of each project, capacity building can simultaneously realize field-level change and sustainability. Clinging to past practices or refusing new approaches due to a lack of precedent is no longer a viable choice for sustainable ODA.

Copyright & Usage Notice

© 2025 Mijeong Kim. All Rights Reserved.

All content in this article—including text, structure, and logical development—is protected under copyright by Mijeong Kim. This article is officially published by BBL Learning. Unauthorized reproduction, distribution, or commercial use of any part of this content without explicit permission is strictly prohibited. When citing this article, please provide proper attribution: Mijeong Kim · BBL Learning, including the original link.

For other uses (e.g., lecture materials, textbooks, commercial redistribution), please contact us at [bbl.learning.org@gmail.com] or via the official contact form.

※ This content may not be collected, crawled, reprocessed, or used for AI training purposes without explicit authorization.

Reference

국가지속가능발전위원회. (2016). 제3차 지속가능발전 기본계획. 대한민국 정부. https://clik.nanet.go.kr/clikr-collection/policyinfo/228/1076/2016/CLIKC2219543121402263_attach_1.pdf

국제개발협력위원회. (2025). 원조를 넘어 연대로: 제4차 국제개발협력종합기본계획(2026‑2030) 초안. 대한민국 기획재정부. https://dala-dala.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/KOSODA.pdf

OECD. (2024). OECD development co‑operation peer reviews: Korea 2024. OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/oecd-development-co-operation-peer-reviews-korea-2024_889c6564-en.html

OECD DAC. (2006). The challenge of capacity development: Working towards good practice. DAC Network on Governance, OECD. https://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/capacitybuilding/pdf/DAC_paper_final.pdf

OECD. (2024). Valuing and sharing local knowledge and capacity: Practical approaches for enabling locally led development co‑operation. DAC Perspectives Paper. https://one.oecd.org/document/DCD%282024%2928/en/pdf

UNDP. (2009). Capacity development: A UNDP primer. United Nations Development Programme. https://www.undp.org/publications/capacity-development-undp-primer

Wikipedia. (2025, January 8). Capacity building. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Capacity_building